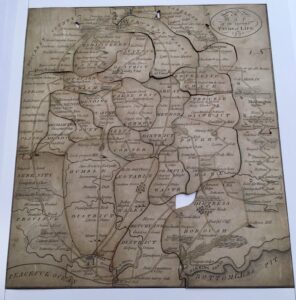

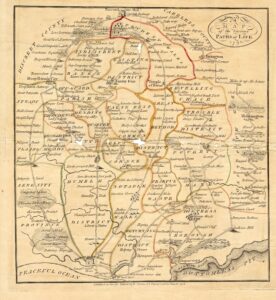

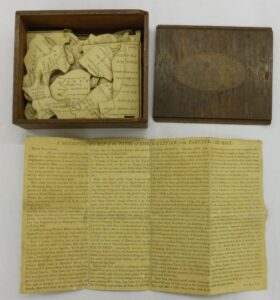

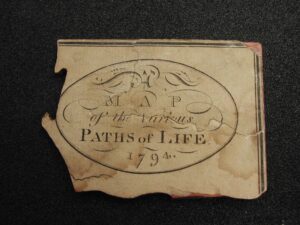

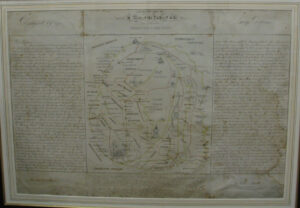

In 1916, Albert Edmunds (1857-1941) recalled “a very curious religious game” that young Friends played with on Sunday afternoons. Born into a Quaker family in Middlesex, England, Edmunds attended the Croyden Friends Boarding School and later taught there before attending university and emigrating to the United States. The game he remembered was based on an allegorical map called “A Map of the Various Paths of Life” created in 1794 by American minister George Dillwyn (1738-1820). Edmunds was familiar with a dissected version of the map (what we call a jigsaw puzzle) that became popular in the late eighteenth century. As an artifact of his Quaker childhood, this map depicts an imaginary landscape fraught with risk and reward for the pious Friend.

“A Very Curious Religious Game”: Spiritual Maps and Material Culture in Early America

The Quaker spiritual journey, often invisible due to its silent, humble and individual nature, is illustrated in this map.

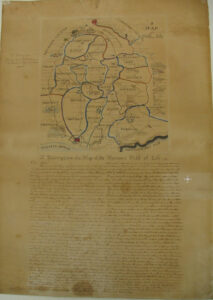

Accompanying the map was a letter by an unnamed parent to his or her children delineating the “various paths to happiness” that Friends walked from early childhood to old age. The letter warned Quaker offspring to remain on the straight and narrow, lest they find themselves in “Off Guard Parish” where “Alluring Bower” and “Sorrow Chamber” were found. The letter counseled Quaker youth to remain watchful. Those who attained “Knowledge Pastureland” to reach “Promotion Mount,” could still make a stop at “Flatterer’s Haunt,” which led to the town of “Braggington” and “Vanity Fair.” Starting out well in life did not guarantee spiritual safety. One could easily be diverted from the “narrow path” and find themselves in “Knave’s Lure, and in great danger of going by Forger’s Hole, to Detection Crevice, and, to the great grief of parents and friends, they have been brought into Conviction Court, sent to Dungeon Bottom and narrowly escape Gallows Hill.” This was one of many pitfalls outlined in the parental letter. The dangers posed to young men were especially highlighted. A sharp turn at “Pausing Window” would land them in “False Rest Common,” where “Idleman’s Corner” led to “Seduction Play-house” and “Bully’s Brothel.” Yet there was hope for salvation. If a Friend reached “Mending Quarter,” they could go from “Faltering Alley” to “Good Resolve Turnstile” and “Bear Cross Road.” Friends confronted a panorama of pathways that meandered from comfort and danger to solace and sin. Choosing the “path of righteousness” would ensure the believer’s journey through life. The letter ended by advising young Quakers to avoid the “many strange and crooked paths” evident in Dillwyn’s map.

Dillwyn’s map and letter were manufactured by William Darton and Joseph Harvey, English Quaker printers and booksellers whose firm would become a leading producer of juvenile ephemera by the nineteenth century. Dissected maps became popular during the eighteenth century when the expanding English empire and improved travel fueled consumer demand for geographical books and maps. It led to an emerging trade in children’s games and puzzles, with themes ranging from history and literature to science and ethics, with geography the most popular topic. Children learned geography by copying and coloring maps, embroidering globes, and memorizing cards. They played with dissected maps, which were usually hand colored on thin sheets of mahogany and housed in a wooden box. At a cost from seven shillings six pence to £1.10 when they first appeared, these items were only affordable to the middling and better sort in England and the United States. The production of Dillwyn’s allegorical map was unusual for Friends who disdained the visual arts as worldly and pernicious. Quaker abhorrence of art makes this image singular at the same time it demonstrates their adaptability to a new mode of educational instruction. Yet Quaker plainness was retained. Dillwyn’s map made use of little color, had few illustrations, contained no human figures, and relied heavily on the written word to convey meaning.

Dillwyn’s map detailed an imaginary world that Friends traversed during their time on earth. It visualized the common Quaker practice followed by believers, or “fellow travelers,” as they journeyed down the “tribulated path.” Friends endorsed a faith based in mindfulness. Religious practice came through prayer and meditation, reading and writing, conversation and worship to enforce the need to live every day in a state of spiritual awareness. Whether dressing in the morning, traveling to meeting, or talking to family members, Quakers strove to be mindful in all aspects of daily life. To maintain conduct consistent with their conviction, Friends deferred to what they called the “still, small voice” within to implant proper demeanor. This phrase exemplified the interior nature of Quaker spirituality and was a guiding principle as Friends labored to sustain their faith. The Quaker spiritual journey, often invisible due to its silent, humble and individual nature, is illustrated in this map.

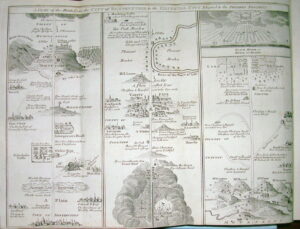

Dillwyn was likely influenced by John Bunyan’s 1678 book, Pilgrim’s Progress, which was made into a dissected version during the cartography craze of the eighteenth century. Christian’s journey, as outlined in Bunyan’s book, includes place names similar or the same to those encountered in the “Map of the Various Paths of Life,” such as “Vanity Fair.” A second inspiration was Stephen Crisp (1628-1692), a first-generation English Quaker who wrote a less well-known tract entitled A Short History of a Long Travel from Babylon to Bethel in 1691. This work documented the travails of an unnamed Friend, who followed “the Light” through a landscape teeming with diversions. Upon reaching Bethel, the traveler attained peace and comfort in his “heavenly habitation.” This book embodied the Quaker approach to piety, which dictated mindfulness to infuse the proper internal state and corporeal behavior. Spirituality as a daily, even hourly activity, required diligence, humility, and patience.

The map of Pilgrim’s Progress was not part of the original book; an enterprising printer produced a version of Christian’s journey in map form in 1778 to meet the commercial demand for geographical representations. While Dilwyn’s map is an imaginary of Quaker practice detailing an empire of the soul, Bunyan’s allegorical vision was based in the Bedfordshire landscape where he was born and bred. A tinker by trade, Bunyan traveled extensively, and his preaching activity took him to villages and hamlets throughout Bedfordshire. Local landmarks became the backdrop to Christian’s journey. One scholar asserts that the “Delectable Mountains” described in Pilgrim’s Progress were the Chiltern Hills; the “Sepulchre” was the Holy Well at Stevington church; and the “House Beautiful” was based on Houghton House built by the Dowager Countess of Pembroke in the early seventeenth century. With Bedfordshire as his template, Bunyan imagined Christian’s pilgrimage teeming with spiritual import. The “Slough of Despond,” similar to the boggy places common to rural England, represented the fears and doubts that mired individuals in sinfulness as they struggled to find the path to salvation.

The Religious Society of Friends advocated a “guarded education” for their children. This format taught them basic skills (reading, writing, and ciphering) but protected them from worldly influences. The education of Quaker children was to be “useful” and “practical” based in moral instruction. Students learned to “regulate every thought and action” to comply with Quaker ideals of plainness in dress, speech, and deportment. Young Friends were to respect their parents, guardians, and teachers and to live harmoniously with their siblings and schoolmates.

The Friends safeguarded their children by founding Quaker educational institutions in England, British North America, and the United States from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. Sarah Tuke Grubb, a Quaker minister and educator embodied the Friends’ approach to a “guarded education.” She asserted that “a religious improvement in the minds of youth” was the principal aim of Quaker schools. Quakers published specialized books for children both for instruction in the classroom and at home. These publications used Quaker theology and practice to teach basic skills. Lindley Murray, an American Friend, wrote English Grammar, Adapted to the Different Classes of Learners in 1795, which combined “moral and useful observations with grammatical studies.” By learning grammar, young minds would be exposed to the “animating views of piety and virtue.” For example, in the section on parsing, he presented phrases such as “let us improve ourselves” and “virtues will be rewarded,” to merge ethical instruction with language acquisition.

Lockean theories of education also impacted Quakers. John Locke’s treatise, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, became a standard text for childrearing, and it had a profound impression on English and American parents in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Locke believed learning for children should be based in play. This prevalent theory of education initiated the production of material objects specifically for children’s use, and maps became a primary teaching tool in the eighteenth century. Booksellers and printers responded to the growing demand for maps by specializing in products for young consumers, such as atlases, map games, playing cards, and puzzles. Thus, children acquired knowledge by playing with geographic objects.

Children’s interaction with the map is evident in the copies made by scholars at the Westtown Friends School in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1799 by Philadelphia Quakers, Westtown was a “select” institution that only admitted Friends who were taught by Friends. The school’s archives contain copies of the map made by scholars. In 1826, Matilda Hogdson, a student from Philadelphia, drew the map; in 1828, Mary Hoopes copied the letter in the wake of the Hicksite Schism, possibly to remind her fellow students of the need for tolerance and unity. In the 1860s, Edwin Thorpe attended Westtown as a teenager. He stayed on at the school as an instructor of Writing and Drawing and, at some point, he sketched a copy of the map. In 1872, he became the first faculty member hired to teach fine art at Westtown. As Quaker institutions evolved, and with their entry into higher education, Friends’ attitude toward art changed. As a visual representation of spiritual practice, Dillwyn’s allegorical map, as a successor to the map of Pilgrim’s Progress, drew upon a popular format to expand the means of the moral instruction for young Quakers in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Sarah Horowitz and Ann Lipton at the Quaker Collection of Haverford College, Andrea Immel at the Cotsen Children’s Library of Princeton University, Mary Brooks at the Esther Duke Archives of Westtown Friends School, James Kessenides of the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University, Alison Clague at Leicestershire Museums and Galleries, and Andrew King of the Nottingham City Galleries and Museums for their help in locating these images as well as background information.

Further Reading

On dissected maps, see Jill Shefrin, Neatly Dissected for the Instruction of Young Ladies and Gentlemen in the Knowledge of Geography (Los Angeles: Cotsen Occasional Press, 1999); Jill Shefrin, The Dartons: Publishers of Educational Aids, Pastimes & Juvenile Ephemera, 1787-1876 (Los Angeles: Cotsen Occasional Press, 2009); and Linda Hanna, The English Jigsaw Puzzle (London: Wayland Publishers, 1972). On Bedford geography, see Vera Brittain, In the Steps of John Bunyan: An Excursion into Puritan England (London: Rich and Cowan, 1928). On Bunyan’s life, see Tasmin Spargo, John Bunyan (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015). On Quaker children and maps, see Judith A. Tyner, Stitching the World: Embroidered Maps and Women’s Geographical Education (Burlington, VT: Routledge, 2015) and Carol Humphrey, Quaker School Girl Samplers from Ackworth (Guildford: Needleprint, 2006). For more on Dilwyn’s map and Quaker education, see Janet Moore Lindman, “‘The pleasures of traveling in Liberty Plains’: Practical Piety and Childhood Education Through Material Culture in the American Quaker Community,” Quaker Studies (forthcoming 2022).

This article originally appeared in June, 2022.

Janet Moore Lindman is Professor and Chair of the History Department at Rowan University. Her book, A Vivifying Spirit: Quaker Practice and Reform Antebellum America, will be published by Penn State University Press in the spring of 2022. Her current research project is on gender and transatlantic Protestantism during the long eighteenth century.