What do you do when you find that a significant painting of early American history, in the collection of a major American gallery, was reported in nineteenth-century British newspapers to have been destroyed in a fire? To be specific: Portrait of John Wilmot by Benjamin West, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1812, sold at auction in 1970 to an American collector, was reported as “totally destroyed” in 1863 on a train bringing the Wilmot family’s possessions from Bristol to London.

Was the Portrait of John Wilmot Destroyed in a Fire?

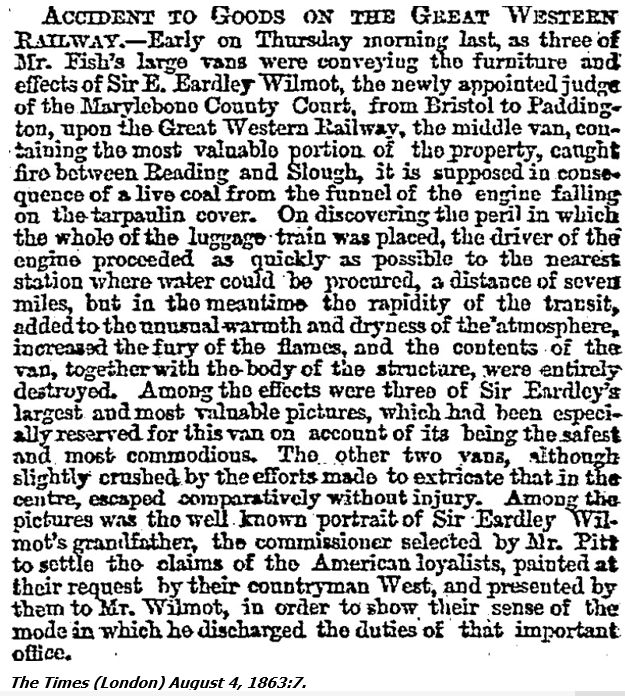

I was shocked to find that British newspapers in early August 1863 described the Portrait being “entirely destroyed” by fire on a railway train.

The picture, in the collection at the Yale Center for British Art, is well known to scholars of early American history. Historian Mary Beth Norton’s graduate work was on the experiences of the American loyalists in the War of Independence––colonials who remained loyal to the British government and were exiled from America by the revolutionaries. In a short paper in 1973, she described Wilmot’s life and focused on the “second” painting behind the figure of Wilmot, which is an allegory of Britain’s beneficence to the loyalists. Since then, books by Simon Schama and Maya Jasanoff, respectively on experiences of Black exiles and of loyalists across the British Empire, also comment on the allegorical “second” painting within the Portrait and the diversity of people shown in it.

With a prior interest in the Wilmot family from my local history work, I was researching from a different perspective: how did the picture come about? The Portrait was painted in London, in the troubled times of Britain’s war with Napoleonic France and continued conflict with the United States about the boundaries with Canada. Wilmot, a member of Parliament and lawyer in Georgian Britain, had led a commission adjudicating compensation for the American loyalists who lost their property or position through the revolution. West came to Britain in 1763 from the American colonies, became the most-favored painter of King George III, and rose to be president of the Royal Academy. During and after the American Revolution, he assisted returning loyalists yet also maintained patriot friends. He saw himself as the “father” of schools of painting in both Britain and America, received students from America, and maintained his links with Philadelphia.

The Portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1812, its full title describing Wilmot’s public service for the loyalists. The Prince Regent and his sons, the Dukes of York and Cumberland, came for a royal viewing, and the artist Joseph Farrington, whose contemporary diary is much used by art historians, wrote that, “The portraits principally occupied his attention, & he continually referred to the catalogue for the names of the portraits, & remarked upon those that were like.” There is no record that the Prince asked about Wilmot, but a newspaper review described West’s “portrait which claims the merit of being an historical painting, from the accompaniments which embellish the subject of the piece.” This description of accompaniments is evidence of the “second” allegorical painting that we see in the Portrait.

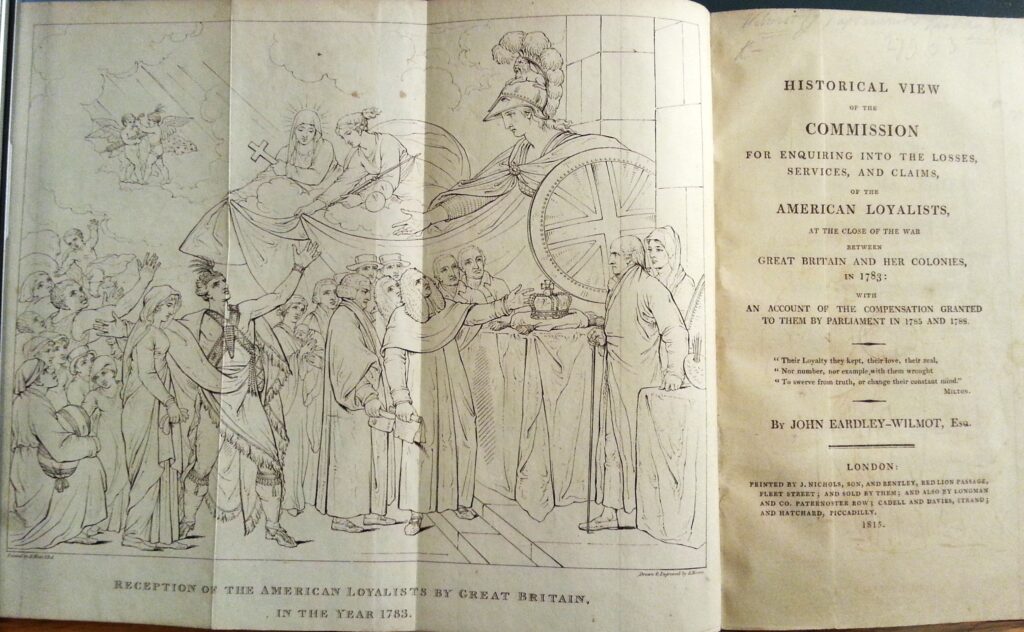

In the year of his death, Wilmot published a book about his work with the commission and included, as a frontispiece, a line drawing titled “Reception of the American Loyalists by Great Britain.” Commentaries originally thought it was drawn from a separate picture by West, but since the Portrait came to public view, it has been considered copied from the “second” painting within the Portrait.

This was the state of play when, late one evening, idly scanning nineteenth-century English newspapers for “Wilmot” on the internet, I was shocked to find that British newspapers in early August 1863 described the Portrait being “entirely destroyed” by fire on a railway train. The Times report may be trusted for veracity, since Sir John Eardley-Wilmot was a judge and would have taken exception to misreporting. Three “valuable pictures,” it said, in the “safest and most commodious” van were “entirely destroyed” in the fire, including the “well-known portrait of Sir Eardley Wilmot’s grandfather, the commissioner selected by Mr Pitt to settle the claims of the American loyalists.”

In my research on the Portrait, I had looked at the web pages of the Yale Center for British Art, which provide excellent metadata documentation of their collection. The Portrait of Wilmot has a bibliography of thirty references, many with further net links. They included the catalog and newspaper reports from the 1970 sale and an analytic article prepared for a special display of the painting in 1983. But there was no mention of the fire. I contacted the Center’s curators and shared my finding of the newspaper reports. The picture’s provenance from the London sale, in the Center’s own records, and the painting’s actual presence in the gallery are at odds with the newspaper archive, which could not be explained.

I worked along several lines of inquiry to explore the newspaper report. First was to relate the frontispiece print in Wilmot’s book with the oil-painted Portrait as a whole. Benjamin West had worked across his career with engravers to produce prints of his paintings—it was important for his income since many of the paintings themselves did not sell. By 1811, West had engaged a young artist, Henry Moses, to engrave prints for a collection of his recent paintings. The technique of outline-engraving that Moses used was faster than fully modelled engravings and it suited the sharply defined figures in West’s work. Moses’ name as well as West’s is in the print collection and also on the frontispiece of Wilmot’s book.

My next approach was to trace the Portrait across time. Little is known of the Portrait since it was displayed at the Royal Academy and before it emerged in 1970. It was not recorded by West’s biographer of 1820, nor in the early-modern record of West’s work by Grose Evans in 1959. It is included in the major catalogue raisonné of West’s work in 1988, but that was well after the auction sale. I’ve found just one direct mention before 1970. Following his work with the American loyalists, Wilmot became active raising money for French émigrés fleeing to Britain during the French revolution. Margery Weiner, a retired civil servant, wrote a history of the French émigrés. In 1966 she gave a talk, serendipitously in the house where John Wilmot had once lived and which has become the local museum. In the talk as later published, she described visiting Wilmot’s descendent, Sir John Eardley-Wilmot, 4th baronet, who was “kind enough to show me the picture in his possession . . . with all the benefits of size and colour.” She did not mention a “second” picture within the painting. This is the only record of viewing Wilmot’s portrait before 1970.

The gallery metadata for the Portrait describes a label on the back, “Property of Late Sir John Eardley-Wilmot,” with the address of Mary Don, in Chenies Row, Chelsea. Visiting the local records office for Chelsea, I found Mary Don at this address as Sir John’s married daughter. I looked up Sir Eardley-Wilmot’s will, which instructed that “ALL the remainder of my property real and personal” should go to Mary, while adding that his nephew Commander John Eardley-Wilmot RN might buy from Mary, if they jointly wished and at an agreed valuation, four pictures: three other named ancestors and “my large picture of the Signing of the Agreement with the American Loyalists.” This last was presumably his name for the Portrait, loosely embracing Wilmot’s work, and would have been the Portrait that went to auction. How these four paintings relate to the three “valuable” family pictures that were apparently destroyed in the 1863 fire is unknown.

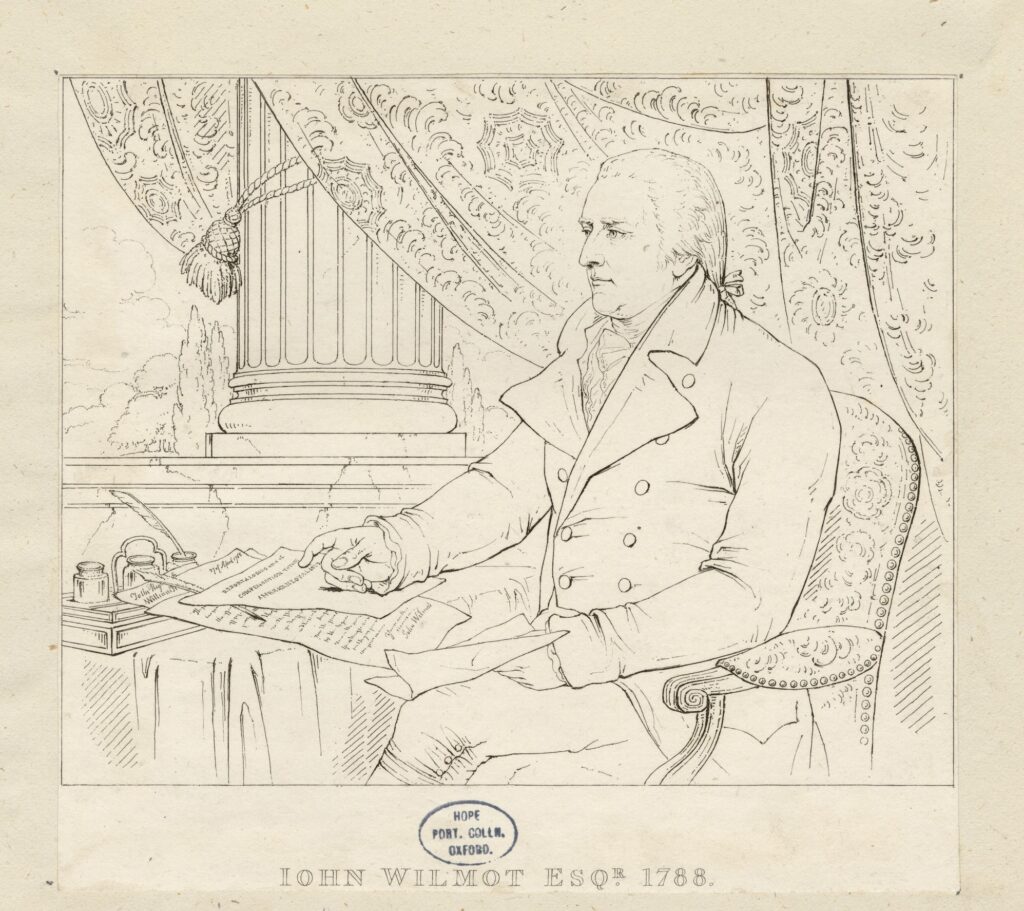

In my research about Wilmot, I found in the catalog of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, a print titled “John Wilmot Esq., 1788.” It is among many thousands of engraved prints, predominantly botanical and zoological, that a benefactor, Dr. Richard Hope, gave to the museum in the 1850s. Wilmot sits in the same pose as the Portrait but, instead of the “second” picture, a background curtain winds around a large fluted column, with trees further distant, while at the front there is no book on the table beside the pen and papers.

Oddly, this print is titled with the date “1788,” the year of Wilmot’s commission report, twenty years before he sat for the Portrait. Perhaps it was created later—but to what purpose? A possibility was for “extra-illustration.” In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries there was a vogue for adding print portrait sheets into existing books. Some portrait prints were created (or reproduced) to supply this market. Dr. Hope similarly gathered his large collection for its completeness as well as for the individual character of the prints.

The Hope collection outline engraving imitates the work of Henry Moses, but it has no names at the base of the print, either of the artist (usually on the left) or of the engraver (usually on the right). Perhaps it’s an unacknowledged copy, but of what? If Wilmot’s Portrait was kept in the family, the image would not have been known. Did Moses make an engraving of Wilmot alone to complement the engraving of the loyalists that became the frontispiece? I have not found any record of this print in online catalogs of the period, although searching through archive boxes in London’s National Portrait Gallery does reveal a photograph of another copy in an unnamed private collection.

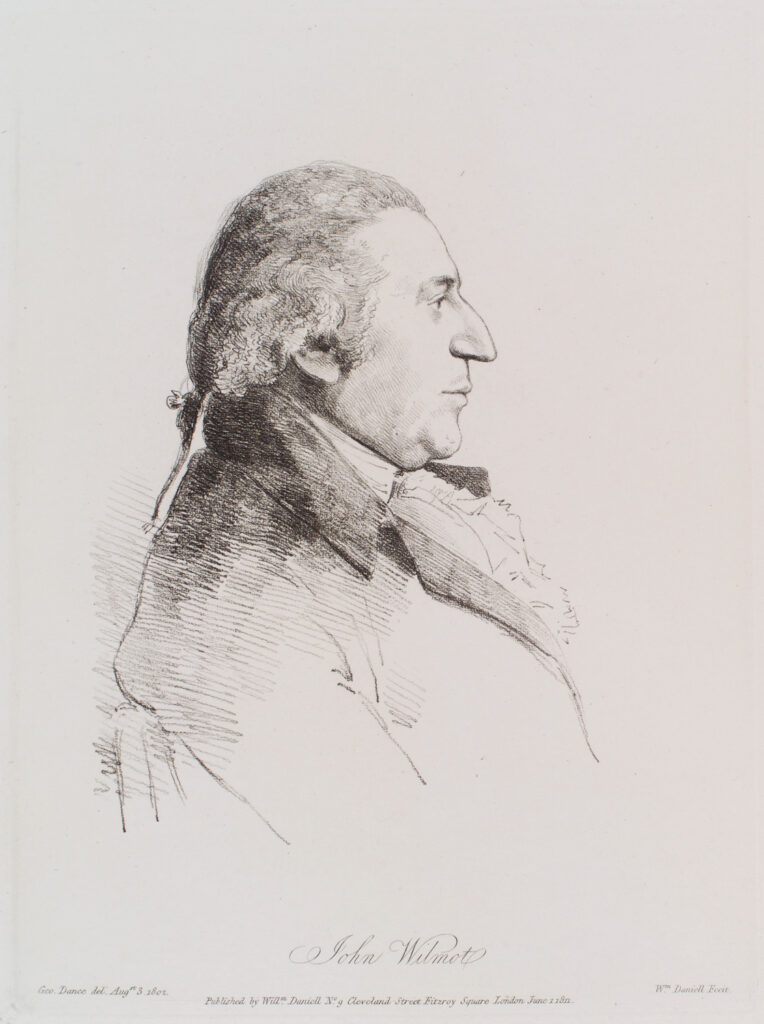

A last possibility for the Portrait was that it was recreated after the fire. Two other portraits of Wilmot come down to us, both earlier than Benjamin West’s and both in profile. He is shown with other members in a composite painting of the House of Commons in 1793 and 1794. It was made shortly before Wilmot stood down from Parliament and he is sitting in the front row, evidently an active member.

A second portrait was drawn by George Dance in 1803 for the series of drawings Eminent Persons, which were later published as etchings by William Daniell in 1811.

In the Portrait, Wilmot wears the black coat and white kerchief of a professional and sits at a desk, hands outstretched to his papers. Although his pose appears rather stiff, in many respects it is like the portrait West painted of himself when he was elected President of the Royal Academy, in 1793. West’s black coat is single-breasted while Wilmot’s is double-breasted. These are formal clothes but contrast with the sitters in most of West’s other portraits (mainly before the 1780s), who are more colorful.

The print of Wilmot in profile by Heckel or Dance, the print of Wilmot at the Ashmolean, West’s oil self-portrait in characterful pose, and the whole scene of the Reception frontispiece print would together have provided sufficient material to re-create the Portrait.

So, did the fire really happen? The Railway Passengers Assurance Company were the main insurers for railway accidents at that time. I searched the board minutes for 1863 through 1864, held at the London Metropolitan Archives, but their insurance only covered bodily harm of people, not for goods. I went to the National Archives in Kew, London, (where the compendious volumes of Wilmot’s Commission are also held) to look for the board minutes of the Great Western Railway Company. For August 5, 1863 I found: “Mr Grierson reported that a Van of furniture belonging to Sir Eardley Wilmot had been destroyed by fire . . . for which a claim has been sent in of £500 for the furniture and £98 for the Van. Instructions were given to . . . offer reasonable compensation for the Van & furniture. But to decline all liability for sundry pictures destroyed which were not insured.”

My opening question is unanswered. I’ve linked the painting with its engraving, searched out parallel images, found sought out evidence for inheritance, and I’ve confirmed the fire. But I haven’t found an explanation. Perhaps the attention of Commonplace readers and new approaches can lead to a resolution.

Further Reading

Note: “John Wilmot” was how Wilmot styled himself up to 1812, when by royal deed he joined his father’s name Eardley to his own surname, becoming John Eardley-Wilmot. His son gained a baronetcy, his grandson Sir Eardley-Wilmot 2nd Bt lost the pictures in the fire in 1863 and the heirs of Sir Eardley-Wilmot 4th Bt sold the Portrait in 1970.

I am grateful to Yale Center for British Art for guidance about the Portrait. Writing mentioned in the text includes: John Eardley-Wilmot, Historical View of the Commission for Enquiring into the Losses, Services and Claims of the American Loyalists at the Close of the War between Great Britain and her Colonies, in 1783: with an Account of the Compensation Granted to them by Parliament in 1785 and 1788 (London: self-published, 1815); Mary Beth Norton, “Eardley-Wilmot, Britannia and the Loyalists: a Painting by Benjamin West,” Perspectives in American History 6 (1972): 119–31; Margery Weiner, John Eardley-Wilmot, A Man of his Time, (London: Edmonton Hundred Historical Society, 1970); Lucy Peltz, Facing the Text: Extra-illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769–1840 (San Marino Calif.: Huntington Library Press, 2017).

This article originally appeared in May 2024.

Mark McCarthy is a graduate of the Institute of Historical Research, University of London, and an historian of Camden Town. Wilmot Place is the (unexplained) name of a local street. Lord Camden upheld democratic rights for the American colonists pre-Independence. A longer article on how Benjamin West’s painting of John Wilmot came about, in the context of British and American history, is awaiting a publisher.