Matt Kish’s Moby-Dick blog began with a sparse preamble: “Because I honestly consider Moby-Dick to be the greatest novel ever written, I am now going to create one illustration for every single one of the 552 pages in the Signet Classic paperback edition. I’ll try to do one a day, but we’ll see.” That same day, August 6, 2009, Kish posted his first illustration.

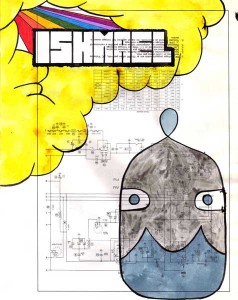

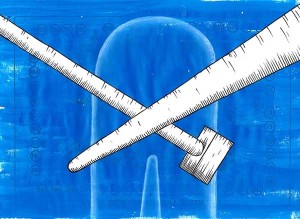

“Call me Ishmael” was the preordained choice for Kish’s page one illustration. We have seen other Ishmaels before, like Rockwell Kent’s patrician Ishmael with the slender nose and sloping brow. In contrast, Kish’s Ishmael is all head, no body: a rectangular lucha libre mask with wide-set eyes and a peaked line of blue ocean waves where his mouth might have been.

Hovering above the Ishmael-icon in the upper left corner of the image, toxic yellow clouds part to issue a single word on a rainbow beam: ISHMAEL.

Kish’s cautious introduction (“we’ll see”) belied his assiduous self-discipline. Kish carved out time for the Moby-Dick project around his full-time job as a librarian and the long commute that bracketed his work day on both ends. Nevertheless, he met each deadline, creating and posting a new drawing every day for over a year and a half on the Website One Drawing for Every Page of Moby-Dick. He was inspired to tackle every page of the book by the contemporary artist Zak Smith, who made a drawing for every page of Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. Kish intended for the Moby-Dick project to be personal: in creating the images, he mined his memory for the imagery of comic books and prog rock album covers that surrounded him in his youth. Kish imagined his audience to be a small circle of family and friends interested in his work, and he did nothing to advertise the project to others. But his project attracted attention almost immediately. He received his first interview request before he completed a week’s worth of illustrations. The interviews multiplied, the links proliferated, and before long, Kish’s Website was attracting a wide and loyal group of online viewers.

Kish recreated Melville’s novel as a psychedelic dream world in which every character, creature, and ship is a monster. Rather than retelling the story of Moby-Dickthrough pictures, as if creating a graphic novel, Kish based each drawing on a short passage from each page, illustrating not just concise plot points and famous quotations but some of Melville’s most exotic figures and similes. Kish created a visual world from each textual fragment in the way that a DJ makes a song from sampled tracks, or a preacher extracts a long sermon from a single scriptural verse.

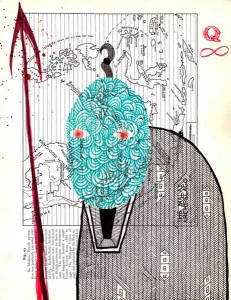

The set of 552 images is impossible to describe as a single body of work, but the illustrations cohere. Recognizable figures and graphic motifs recur and interlace through otherwise alien and disparate fantasy landscapes. The blog’s followers learned Kish’s visual vocabulary for Moby-Dick as he produced it: we came to recognize Queequeg by the azure of his intricate tattoos, and Ishmael by that laconic mask.

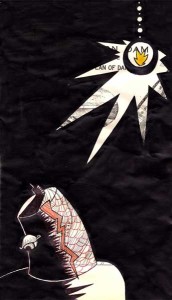

Ahab is a helmet—blunt, hulking, and riveted like an ironclad.

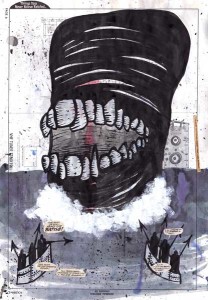

The white whale himself is never the same: sometimes he is a fairy-tale sea monster, sometimes a white mass streaked with black veins, sometimes an enormous mouth crammed with lurid human molars, sometimes a sinuous figure traced with swirls as fine and intricate as lace.

This Moby-Dick is not, to put it mildly, a work of realism or rigorous historical interpretation. Matt Kish was not thinking about the history of American whaling when he illustrated Moby-Dick. He told me that he actively avoided doing any kind of historical research at all while creating the illustrations. “It’s not that I don’t have any specific interest in the nineteenth century, but I made no attempts to be historically accurate… Rather than try to create this historically accurate version of Moby-Dick, I really wanted to go very, very internal, and create an almost symbolic and fantastic rendition.”

Kish’s Moby-Dick chronicles the kind of experiment that Thoreau tried out at Walden Pond: an experiment in living deeply within a world that is both bounded and infinitely rich in meaning and detail. The 552 pages of Melville’s book became Kish’s world. Matt Kish has a knack for locating echoes of the nineteenth century in the technology, aesthetics, and humor of the twenty-first. He brings the arcane world of nineteenth-century whaling into camaraderie with the esoterica of twentieth and twenty-first century cultures: machines, comic books, street art, and album covers. Kish even practices his alchemy on the genre of the blog itself, creating a daily marvel out of an arbitrary assignment—one drawing for every page, every day. In a blogosphere that rewards the story of the minute, Kish’s project is a monument to sustained attention, rigorous discipline, and long, old, thoroughly material books.

It is hard not to make something out of the fact that Matt Kish is a librarian. After all, it is a Sub-Sub-Librarian who introduces the “Extracts” at the beginning of Moby-Dick: “…this mere painstaking burrower and grub-worm of a poor devil of a Sub-Sub appears to have gone through the long Vaticans and street-stalls of the earth, picking up whatever random allusions of whales he could anyways find in any book whatsoever, sacred or profane.” Before Kish started his project, he said he personally identified with the Sub-Sub-Librarian more than with any other character in the novel: “This nameless person assembling all of these mosaic pieces of information: it always seemed like a curious way of introducing the novel to me. I found it endlessly fascinating to read all of these extracts and put them together in a different order. I could see myself as that kind of explorer—not only through Moby-Dick but in general. That was, up until this project.” After the page-a-day project, though, Kish felt he had established a personal relationship with the whole novel, and not just with the Sub-Sub.

Whether or not Kish still identifies with the Sub-Sub, they have much in common. It might even be said that they share certain extraordinary library practices. The “poor devil of a Sub-Sub” who introduces the Extracts had become “hopeless” and “sallow,” but there were adventures in his past. He had been a librarian in the way that Indiana Jones was an archaeologist: he traveled worldwide to collect his whaliana. Kish is by no means hopeless or sallow, but like Melville’s Sub-Sub, he also started his project with a collection that he culled and saved over several years: a supply of found paper on which he drew most of the Moby-Dick illustrations.

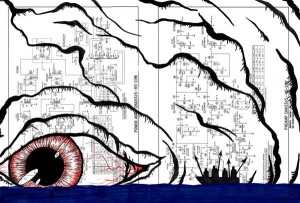

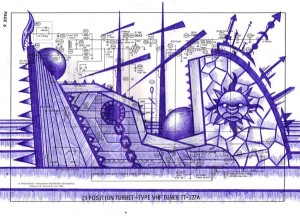

Kish acquired his own trove of extracts long before he began the Moby-Dick project, and his library—like the Sub-Sub’s—is the trophy of a long and varied adventure in collecting. He worked in a used bookstore during grad school and rescued visually interesting pages from books that were doomed for the trash heap. Kish gravitated toward orphaned repair manuals, engineering textbooks, and anything that featured elaborate and inscrutable schematics. During the bookstore years, Kish did not have a purpose in mind for the growing stack of pages, but he began using them as soon as he started illustrating Moby-Dick. He told one interviewer that his earliest illustrations were done on the pages of obsolete electronics repair guides. “Something about those old diagrams fascinates me because their symbols and all those lines and drawings and letters look almost alchemical to me. Magical. So the thought of all that unfathomable information, a bit buried but lurking just beneath the paint and ink really spoke to me. It hinted at the deeper themes and mysteries of Melville’s novel as well as the mysteries lurking beneath the sea.”

Most of the diagrams are barely visible underneath the illustrations—a mumbling hint of flow-chart bubbles, arrows, tables, and numbers under boldly colored monsters that demand all the attention.

Sometimes, the found paper works in direct service of the illustrations. The image for page 94 illustrates Ishmael’s description of the foggy weather on the morning he and Queequeg boarded the Pequod and sailed out from Nantucket harbor: “It was nearly six o’clock, but only grey imperfect misty dawn, when we drew nigh the wharf.” The stylized clouds and muted sun are drawn on top of a weather map showing precipitation and pressure centers: weather illustrating weather.

More often, the relationship between Kish’s illustration and the found paper is occult. But even the most alien diagrams sometimes accrete meaning in Kish’s illustrations: flow-chart arrows and bubbles start to resemble harpoons and whales, and the flat page dissolves through the infinite regress of whales and harpoons, whales and harpoons.

For Kish, the printed matter in the background of his illustrations represents and preserves a world of print culture that is being washed away by digital information and imaging. Digitally created imagery “leaves me cold” says Kish, who cherishes analog print technologies. “My decision to use predominantly found paper from old books—most of which I have picked up at the used bookstore, but also in library discards—[was] a real overt attempt to connect the art and imagery I was creating to the world of print …. I felt it was very important that the viewer would be consciously aware of the print behind the illustrations and the relationship of the image that I was creating to that older, more hand-made approach to creating stories.”

These days, Kish sees a lot more books headed for the trash heap, as libraries work to build and shore up digital collections. He is no Luddite—he appreciates the power of digital resources—but he believes that books and analog print culture have not yet outlived their usefulness. “I see bin after bin after bin of books being sent out the back garage of the library, no longer useful. I thought it was important to do at least a symbolic gesture to this world that did exist and does still matter.”

Discarded books are suggestive and melancholy, not only as artifacts of a receding print culture, but as repositories for a kind of knowledge deemed no longer useful. The books that Kish rescued were marked obsolete not just because they were books, but because they were manuals or textbooks about out-of-date technologies. Discarded books embody the death of utility, the obviation of hard work and hard-won knowledge, but are they obsolete yet? These books raise questions: Have they outlived their usefulness—for what, and according to whom?

As objects that provoke questions about utility and obsolescence, Kish’s rescued diagrams resonate with one of the novel’s strangest qualities: Moby-Dick anticipates the obsolescence of American whaling, and serves as a premature shrine to an industry that had not yet disappeared.

Herman Melville went whaling in 1841, during the boom years of the industry. He shipped on the maiden voyage of the Acushnet, one of the whaling fleet’s newest and biggest vessels. Whaling was one of America’s first global industries and a major driver of domestic industrialization: oil produced by the American whaling fleet lubricated industrial machinery and lit homes and factories in growing cities.

The industry was never more prosperous in the United States than during the years that Melville experienced and wrote about the industry. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, only 324 vessels left American ports on whaling voyages, but in the 1840s, the United States dispatched more than 2,300 whaling voyages. But the booming industry ground to a halt around 1860, when a huge portion of the whaling fleet was destroyed in the Civil War. Confederate cruisers sank or captured at least forty-six whalers, and the United States government requisitioned at least forty more to sink in southern harbors in an attempt to blockade ports. (It did not work: the sunken ships—the Stone Fleet that Melville eulogized in his 1866 collection of Civil War poetry—actually served to deepen the channel.)

The whaling industry might have recovered from the disruptions of war, but the devastation of the fleet coincided with the discovery of the resource that would supplant whaling: petroleum. Oil was struck at Edwin Drake’s well in Titusville, Pennsylvania in August of 1859, and the petroleum boom began. By the end of the nineteenth century, the whaling industry had dwindled almost to oblivion.

Not that Melville knew any of this would happen when he wrote Moby-Dick. Technologies are made obsolete by their replacements, not by any palpable sense of doom, and in the decade between Melville’s own 1841 whaling voyage and the publication of the novel in 1851, whale and sperm oil were still considered superior illuminants and industrial lubricants. Despite that, Moby-Dick focuses on the elements of the whaling industry that were old, worn, and obsolete in their ways—as if he were describing an industry that had already entered its obsolescence.

For example, Nantucket had been the center of the American whaling industry in the eighteenth century, but by the 1820s New Bedford had eclipsed the island port as the capital of the industry. Ishmael passes through busy New Bedford, but decides to ship out of Nantucket out of a sense of nostalgia for that port’s earlier prosperity: “For my mind was made up to sail in no other than a Nantucket craft, because there was a fine, boisterous something about everything connected with that famous old island, which amazingly pleased me. Besides though New Bedford has of late been gradually monopolizing the business of whaling, and though in this matter poor old Nantucket is now much behind her, yet Nantucket was her great original—the Tyre of this Carthage; —the place where the first dead American whale was stranded.” Though the whaling industry loomed large in the contemporary United States economy, Ishmael treated his own whaling voyage as if it were a voyage backward in time.

The ship Pequod, too, was a vestige of an earlier phase of the whaling industry: “She was a ship of the old school, rather small if anything; with an old-fashioned claw-footed look about her.” She was a ship trophied by past hunts, and named after “a celebrated tribe of Massachusetts Indians, now extinct as the ancient Medes.” Matt Kish’s portrait of the Pequod evokes its inimitability and intricacy, but Melville’s own image is at least as fantastic.

The Pequod was a far cry from the huge, up-to-dateAcushnet Melville knew from his own whaling voyage. In creating the Pequod, Melville went far outside his own experience to dream up a ship “more than half a century” old, a ship not on its maiden voyage but on its death voyage. Melville was no soothsayer: he did not prophesy that whaling would crash within a short decade of his book’s publication. But Moby-Dick‘s peculiar focus on obsolescence forestalls any optimism about the sustainability of industrial success and imperial expansion. In bringing to light the obsolete aspects of a thriving industry, Moby-Dick offers a premature eulogy and a warning: obsolescence is always built in.

I learned about One Drawing of Every Page of Moby-Dick when Matt Kish was about halfway through his illustrations for the novel. I, too, was about halfway through my own long engagement with Melville and Moby-Dick: a dissertation on the cultural history of the United States whaling industry through its heyday, decline, obsolescence, and commemoration. I checked the Website every day, and every day I was reminded of the power of daily practice. Checking for a new illustration on Kish’s Website, in fact, became a daily habit, something like a threshold ritual. Each fresh illustration cleared the static noise of online distraction and propelled me back into my own work. The images inspired me through their beauty and insight, and they testified to the satisfaction of the met deadline.

For Kish, the production schedule was relentless, but for viewers, the experience of reading the novel through his illustrations was slow—much slower than reading online news stories that appear and disappear almost instantly, like bubbles in a pot of boiling water. In reality, I was racing through the novel out of order as I wrote and revised my own dissertation chapters. Through Kish’s Website, though, I was able to imagine reading Moby-Dick for the first time, working through the novel slowly, day by day.

At first, I thought of Kish’s project as an experiment in seriality, a thoroughly nineteenth-century publication practice. Serialized publication of novels in the nineteenth century constrained authors through deadlines, space requirements, and the calculation of suspense in service of newspaper sales. Kish built in his own arbitrary constraints: every page, every day. No one held him accountable to his own rules, but he faced those deadlines like a hardened journalist.

Kish’s project was a serial in form as well as in practice: each illustration took roughly the same form, appearing on the blog in the same place at the top of the page, but every day the illustration was completely new. The illustrations for the “Cetology” chapter brought a new whale every day for one week, during which Kish created some of his most virtuosic drawings. The seriality of Kish’s whales mirrored the seriality of Ishmael’s whimsical classification of whales into folios, octavos, and duodecimos. The whales are unbelievably intricate and individuated. The finback whale resembles a military plane in camouflage colors with fins like metal plates dotted with bolts. The thrasher whale is an unnerving green coil of intestines, and the sulphur-bottom whale is worm-like, decorated with rounded tiles that resemble cobblestones.

But it was not narrative suspense, exactly, that kept me coming back to the Website: I was transfixed by the spectacle of productivity. I suppose my curiosity to see how Kish would meet each brutal deadline was a form of narrative suspense, and it seemed to have been that way for many other loyal viewers. Kish said that he received unanimously positive feedback through the Website, and that most people remarked on the huge ambition of the project. “[Most people’s] first impression was simply stunned disbelief at the ambition… The farther I got into the project I got all this credibility: ‘This guy’s already done a hundred pages, it’s the real deal.’ That stunned disbelief would turn into: ‘he’s really going to do it; he’s really going to make it.’ “

Kish said that he began the Moby-Dick project in part because he hoped to loosen up his style and learn to draw faster. He had made intricate drawings and illustrations his whole life, but he was frustrated that each piece took him so long to make. He thought that the daily deadline would speed him up by forcing him to simplify. That strategy worked for a very short while: the first several images are simple and abstract, like the “Call me Ishmael” image that opened the project. But Kish fell quickly into his old habit of making intricate illustrations. “But my natural tendency in drawing has always been far, far too detailed, overly detailed. Horror vacui: it’s not quite a fear, but I do have a real natural tendency to fill all empty space with lines and textures and patterns. So I started the project, and things started out very abstractly and I was able to simplify things. But near the end I couldn’t control my natural tendency to overrender things to fill space with patterns and textures. And so in the last fifty pages you can see that coming back. But that’s a good thing, because as an artist it made me reconnect with that [habit]. It really is the way I like to draw and even though it’s slow and stultifying and static, it feels very, very natural to me.”

It is apt that an artist who abhors white space would choose to illustrate Moby-Dick, and unsurprising that the novel would work through him to reinforce that fear of the void. It is poignant, too, that the novel nurtured Kish’s tendency toward difficult, detailed work. Kish’s drive to fill white space is responsible for some of his most wondrous and emotionally affecting illustrations. The illustration for page 402 depicts the moment when the fearful ship-keeper Pip leapt out of a whaleboat during a chase and was abandoned for a terrifying stretch of time in open sea while the boat carried on with the hunt. Pip never recovered his sanity after those moments alone in the ocean: “The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs.”

That last sentence of this passage is excessive—too many heaps, orbs, eternities, and strange shapes—but in its overindulgence it is also beautiful. The verbal convolutions of the passage mimic the warping and twisting of Pip’s mind as he went insane on the open sea. After Pip’s ordeal, the crew of the Pequod considers him an idiot, but Ahab recognizes the note of divinity in his madness. Kish’s illustration imparts some of Ahab’s empathy, transmitting the experience of simultaneous wonder and terror that Pip experienced when the sea “drowned the infinite of his soul.” The illustration gives us Pip through the metonym of his vulnerable eyeball, beset by creeping and snarling sea monsters, some of which only come into view after you stare at the image for a long time. Kish wrote on his blog that the image took him four days to create (by this point in the project, he had begun working ahead whenever he could, so he could afford to create intricate illustrations while still meeting the daily deadline). A simple, swiftly-executed image would have conveyed neither the sublime terror of Pip’s experience nor the reader’s experience of Ishmael’s swarming narrative style. Kish’s perfectly overwrought illustration does both.

Kish finished his project in January of this year. The illustration for his last page mirrored “Call me Ishmael” with the same Ishmael-icon, but with “ISHMAEL” swapped out for “ORPHAN” to reflect Ishmael’s status as the sole survivor of the Pequod‘s wreck: “On the second day, a sail drew near, nearer, and picked me up at last. It was the devious-cruising Rachel, that in her retracing search after her missing children, only found another orphan.”

The symmetry of the first and last page is gratifying, but watching Kish come to the end of his project was bittersweet for us viewers who had lived through the novel in concert with the project.

Partway through his project, Kish drew up a book contract with Tin House Books to publish the whole set of illustrations. The book comes out this fall, and One Drawing for Every Page of Moby-Dick will become one of those solid, substantial books that Kish celebrates in his work. For those of us who followed the project as it unfolded, the book will be a souvenir. The voyage has ended.

All illustrations are by Matt Kish, to be published in October 2011 under the title Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page of Moby-Dick by Tin House Books.

Further reading

Matt Kish was inspired to illustrate every page of Moby-Dick by the artist Zak Smith, who illustrated every page of Gravity’s Rainbow, by Thomas Pynchon. Those illustrations are collected in Pictures Showing What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow (Berkeley, Calif., 2006).

For a thorough economic history of the United Stated whaling industry, I rely on In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 by Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter (Chicago, 1997). The New Bedford Whaling Museum and the museum at Mystic Seaport house and exhibit the most important artifacts and archives of American whaling history.

The story of natural resource extraction continues with Brian Black’s discussion of the discovery and development of the American petroleum industry in Petrolia: The Landscape of America’s First Oil Boom (Baltimore, 2000).

Elizabeth Schultz offers an overview and trenchant analysis of twentieth-century illustrations of Moby-Dick in Unpainted to the Last: Moby-Dick and Twentieth-Century American Art (Lawrence, Kansas, 1995).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.1 (October, 2011).