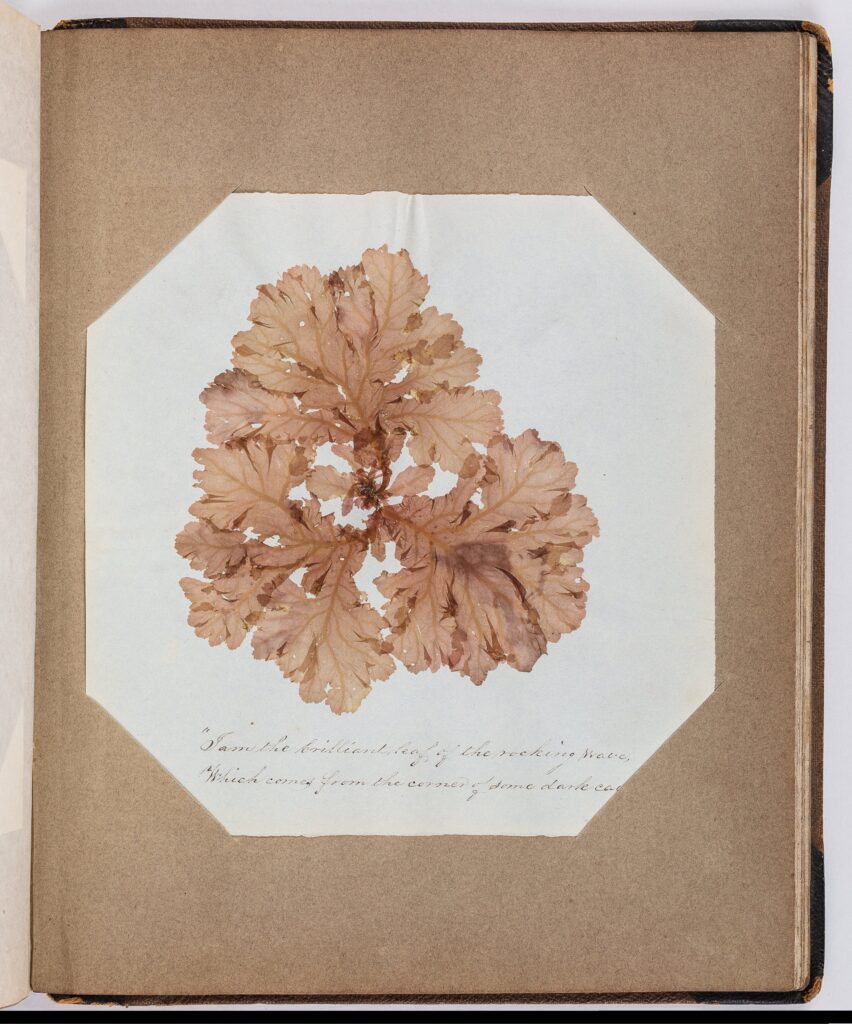

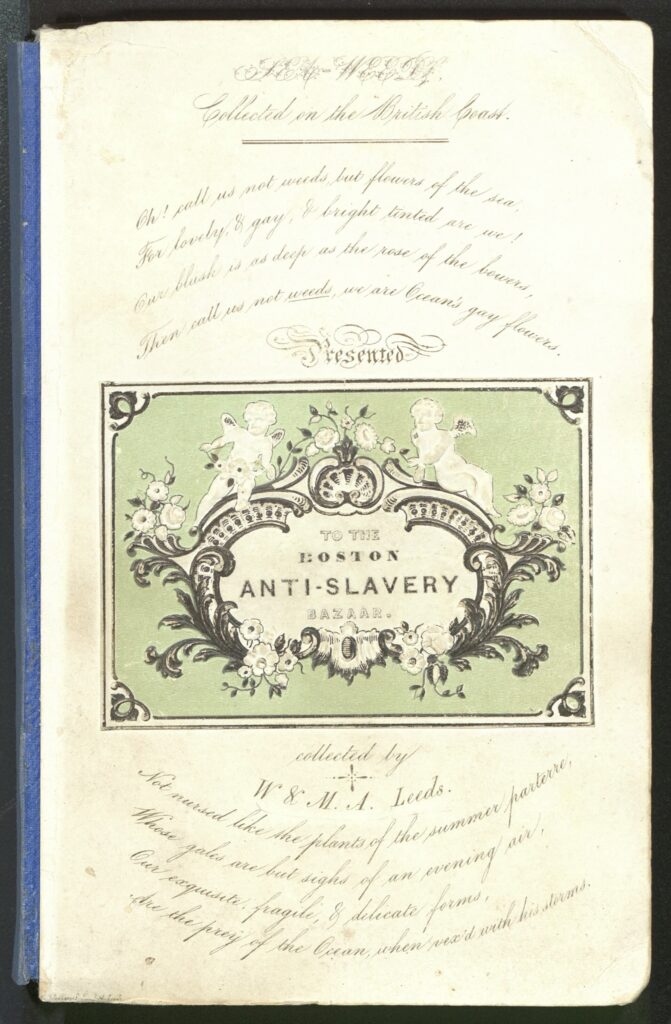

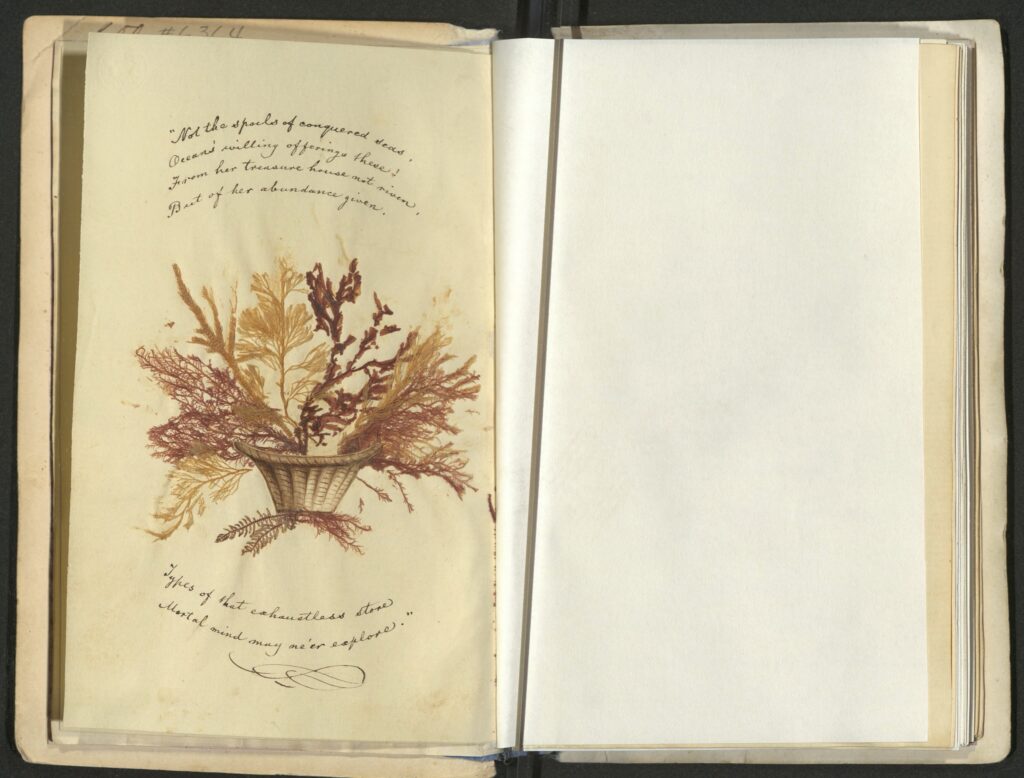

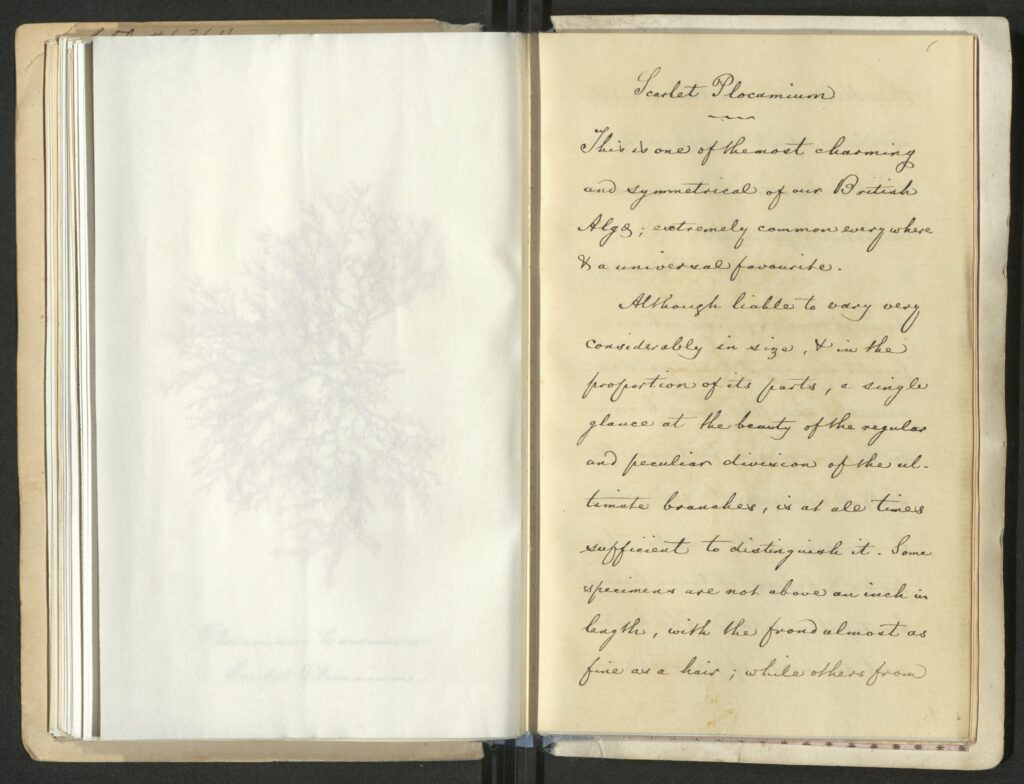

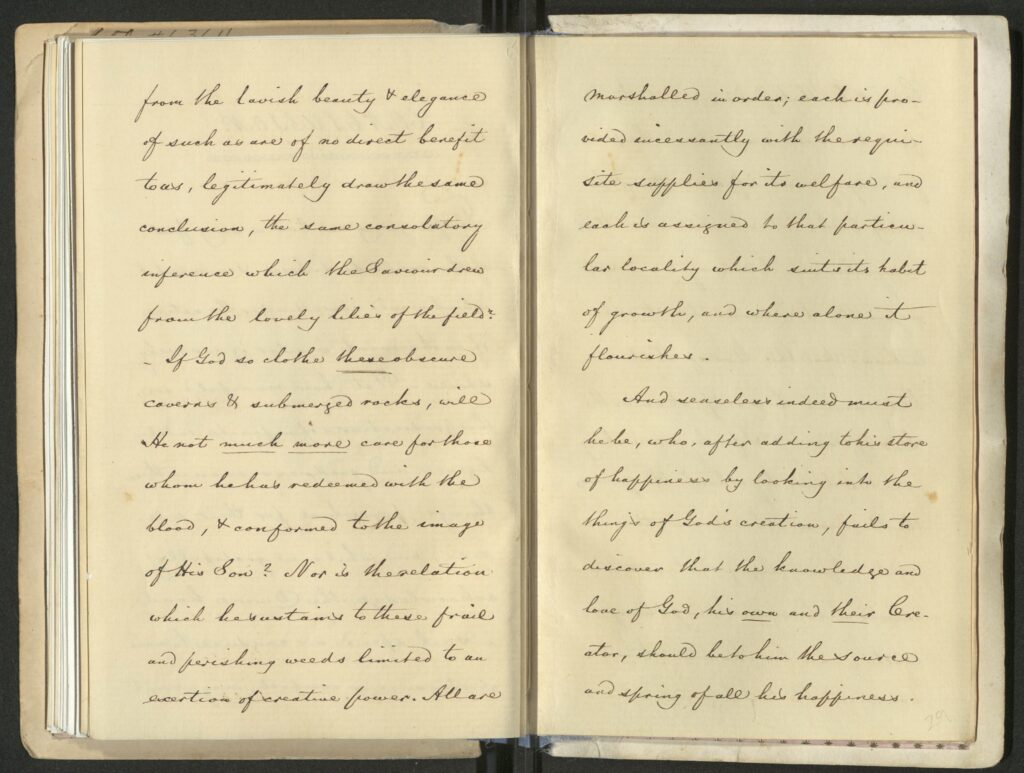

Like the seaweed which addresses readers of The Liberator above, the specimen in the Allens’ album is treated as something akin to the human body (or at least its clothes), and then, as proof of God’s word. Thus, we see that seaweed collection at the anti-slavery fair was not simply an extension of a larger scientific trend or craze. Rather, abolitionists like William and Mary King Allen used the seaweed album to reflect on their own state of exile, to critique slavery’s relationship to systems of scientific knowledge production, to uplift their marriage, and to find religious promises in the obscure and submerged.

Further Reading

A Singularly Marine & Fabulous Produce: The Cultures of Seaweed (New Bedford: New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2023).

Stephen Hunt, “‘Free, Bold, Joyous’: The Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid-Victorian Writers,” Environment and History 11:1 (Feb 2005): 5-34.

Molly Duggins, “Pacific Ocean flowers: colonial seaweed albums” in The Sea and Nineteenth-Century Anglophone Literary Culture, ed. Steve Mentz and Martha Elena Rojas (New York: Routledge, 2017), 119-34.

Maria Zytaruk, “Preserved in Print: Victorian Books with Mounted Natural History Specimens,” Victorian Studies 60 (2018): 185-200.

Sasha Archibald, “Love and Longing in the Seaweed Album,” The Public Domain Review, March 9, 2022.

William G. Allen, The American Prejudice Against Color: An Authentic Narrative, Showing How Easily the Nation Got Into an Uproar (London: W. and F. G. Cash, 1853).

R. J. M. Blackett, William G. Allen: The Forgotten Professor,” Civil War History 26:1 (1980), 39-52.

Teresa A. Goddu, Selling Antislavery: Abolition and Mass Media in Antebellum America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Britt Rusert, Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2017).

This article originally appeared in October 2024.

Charline Jao is a graduate student in the Literatures in English department at Cornell University. Her research on nineteenth-century abolitionist print culture has appeared in American Periodicals and the Cornell Rural Humanities Pamphlet Collection, and is forthcoming in Comparative Literature.