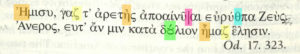

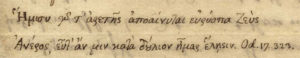

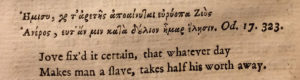

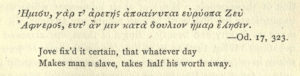

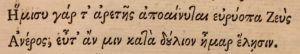

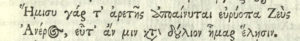

Apart from the legacy of typographical errors, we might still wonder about the appropriateness of Jefferson’s quotation from Homer and Pope for his purposes in Query XIV. Drawing on Longinus and Plato, Pope—or, more accurately, the scholars Elijah Fenton and William Broome who assisted Pope with the actual translation of Greek—suggest in the notes to their translation that Homer’s “very remarkable sentence” about slavery’s emasculating effects is “commonly found to be true.” Jefferson, too, plays on the conventionality of this epic wisdom when he contrasts what he considers the intellectual and moral achievements of Roman and Greek slaves against their African counterparts. Even so, despite Jefferson using Homer to solidify and adorn his argument about slavery, Homer, at least lexically, seems to have been relatively uninterested in slavery. As W. B. Stanford comments in his twentieth-century edition of the Odyssey, “references to slavery and slaves” occur significantly less frequently in Homer “than in later Greek.” Indeed, Stanford counts only seven instances of variations of δούλιον—the word in Jefferson’s quotation for slave—in all of Homer’s writing.

In drawing from Homer, then, we might accuse Jefferson of an (historical) presentism. Jefferson invokes Homer not on Homer’s own terms but as part of an undifferentiated classical world upon which a modern, European concept of a racial hierarchy depended. In other words, classical learning, for Jefferson, Thomson, and their peers, served to define blackness while subtly enacting (with ironic effect) their own whiteness. Appreciating this history can help us understand not only Jefferson’s own definition of race but also, for instance, the nuances in the debates 120 years later between Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois about whether African Americans should bother studying Greek and Latin in the aftermath of slavery and Reconstruction. At issue is not who can or cannot learn Greek. Rather what seems to matter is who can claim racial kinship through Greek and what meaning resides in the form of classical learning. That, as the checkered history of the Greek in Notes suggests, is the (racial) difference that Greek makes.

Acknowledgments

I could not have put together all of the pieces in this history on my own. Leah Price was a terrific guide through the detective process of British book history. Ann Blair gave some very helpful citations about the lack of Greek fonts in the U.S. in the eighteenth century. And Hope Mayo at Houghton Library provided crucial technical wisdom on the identification of the Greek font in Notes. At Common-place, Hunt Howell and Anna Mae Duane offered indispensable feedback on drafts of the essay. Jackie Penny assisted me in tracking down the many images I have here.

Further Reading

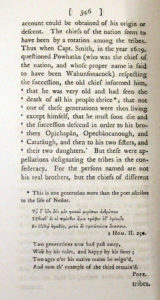

A good starting place to appreciate the sheer number of editions of Notes on the State of Virginia is Coolie Verner, A Further Checklist of This Separate Editions of Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia (Charlottesville, Va., 1950) and Coolie Verner and P. J. Conkwright, “The Printing of Jefferson’s Notes, 1793-94,” Studies in Bibliography 5 (1952): 201–3. More recently, several authors have investigated Jefferson’s punctilious attention to the printing of his books and the books that he purchased: Gordon S. Barker, “Unraveling the Strange History of Jefferson’s ‘Observations Sur La Virginie’,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 112:2 (2004): 134–77; Alice H. Lerch, “Who Was the Printer of Jefferson’s Notes?” in Bookmen’s Holiday: Notes and Studies Written and Gathered in Tribute to Harry Miller Lydenberg, ed. Deoch Fulton (New York, 1943): 44–56; Eric Stockdale, “John Stockdale of Piccadilly: Publisher to John Adams and Thomas Jefferson” in Author/Publisher Relations during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, eds. Robin Myers and Michael Harris (Oxford, 1983): 63–87; David R. Whitesell, “Thomas Jefferson and the Book Arts,” Printing History 24:2 (2005): 3–24. In 2014, John O’Brien and Brad Pasanek at the University of Virginia also put together a useful online edition of Notes that pairs a transcription of the text with page images from Jefferson’s copy of Stockdale’s 1787 printing and the French 1784-1785 edition. This edition is available here. It uses the digitized copy of Jefferson’s copy of Notes from UVA, available here. The manuscript of Notes is available from the Massachusetts Historical Society. The quotation in Greek appears on page 86 of the manuscript.

If you are interested in Jefferson’s knowledge of and interest in the classics, a good starting place is a collection of essays edited by Peter S. Onuf and Nicholas Cole: Thomas Jefferson, the Classical World, and Early America (Charlottesville, Va., 2011). As I mention above, Emily Townsend Vermeule identifies one of Jefferson’s errors explicitly in “Jefferson and Homer,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 137:4 (December 1993): 689–703. The meaning of the classics for the educated elite in the eighteenth century is carefully explained in both Caroline Winterer’s The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780-1910 (Baltimore, 2002) and Carolyn D. Williams’s Pope, Homer, and Manliness: Some Aspects of Eighteenth-Century Classical Learning (London, 1993).

I gathered information on Phillis Wheatley’s education from Vincent Carretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens, Ga., 2011). Carretta speculates on Wheatley’s lack of knowledge of Greek on page 40. On Jefferson’s (lack of) criticism of Wheatley, see William Huntting Howell, Against Self-Reliance: The Arts of Dependence in the Early United States (Philadelphia, 2015): 46-81. For a sense of debates about race and the classics, I am indebted to Sarah Wagner-McCoy, “Virgilian Chesnutt: Eclogues of Slavery and Georgics of Reconstruction in the Conjure Tales,” ELH 80:1 (March 15, 2013): 199–220. The footnote from W. B. Stanford is on page 291 of volume two of The Odyssey of Homer, ed. W. B. Stanford (London, 1948). The footnote by Alexander Pope’s scholarly counterparts is from page 163 of volume four of Alexander Pope, The Odyssey of Homer (London, 1726).

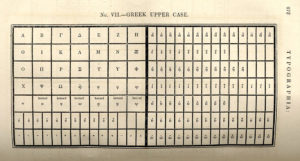

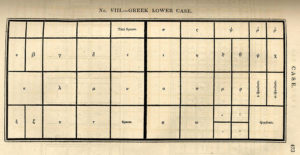

To figure out who did the printing for Stockdale and what type they used, I consulted both primary accounts of eighteenth-century printers and twentieth-century histories of the changes in Greek fonts. A crucial clue in figuring out Stockdale’s printer was the list titled “Books Printed for John Stockdale, Piccadilly,” which is bound in the back of Houghton Library’s copy of Hester Lynch Piozzi, Retrospection: or A Review of the Most Striking and Important Events, Characters, Situations, and Their Consequences, which the Last Eighteen Hundred Years Have Presented to the View of Mankind (London, 1801). With the Hansards in mind, indispensable primary accounts were Luke Hansard, The Auto-Biography of Luke Hansard: Printer to the House, 1752-1828, ed. Robin Myers, Printing Historical Society Publication, no. 15 (London, 1991); T. C. Hansard, Typographia: An Historical Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Art of Printing; with Practical Directions for Conducting Every Department in an Office: With a Description of Stereotype and Lithography. Illustrated by Engravings, Biographical Notices, and Portraits (London, 1825); Philip Luckombe and William Caslon, A Concise History of the Origin and Progress of Printing; with Practical Instructions to the Trade in General (London, 1770); Edward Rowe Mores, A Dissertation upon English Typographical Founders and Founderies (1778). With a Catalogue and Specimen of the Typefoundry of John James (1782), eds. Henry Carter and Christopher Ricks (London, 1961). I supplemented these with biography and general history of printing at the end of the eighteenth century: Ellic Howe, The London Compositor: Documents Relating to Wages, Working Conditions and Customs of the London Printing Trade, 1785-1900 (London, 1947); D. F. McKenzie, Making Meaning: “Printers of the Mind” and Other Essays, eds. Peter D. McDonald and Michael F. Suarez (Amherst, Mass., 2002); Talbot Baines Reed and A. F. Johnson, A History of the Old English Letter Foundries: With Notes, Historical and Bibliographical, on the Rise and Progress of English Typography (London, 1952); J. C. Trewin and Evelyn Mansfield King, Printer to the House: The Story of Hansard (London, 1952).

In identifying and tracing Greek fonts, the single most invaluable resource is the incredibly careful catalog and description by J. H. Bowman: Greek Printing Types in Britain: From the Late Eighteenth Century to the Early Twentieth Century (Thessaloniki, 1998), which is based on a 1988 dissertation of the same title at the University of Reading. The essays by John A. Lane and Bowman in the volume edited by Michael S. Macrakis also provided some useful information about the changes in Greek fonts as well: Greek Letters: From Tablets to Pixels (New Castle, Del., 1996). An older volume produced by the Printed Books Department at the British Museum also provided some useful examples of Greek fonts: Greek Printing Types, 1465-1927: Facsimiles from an Exhibition of Books Illustrating the Development of Greek Printing Shown in the British Museum, 1927 (London, 1927). I also consulted Klimis Mastoridis, “Cutting and Casting Greek Types in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century,” Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 81 (2006): 306–41; Meyer Reinhold, Classica Americana: The Greek and Roman Heritage in the United States (Detroit, 1984).

If you, dear reader, are still here, I imagine you are of hearty enough stock to be interested in seeing what Greek fonts looked like before their simplification at the end of the eighteenth century. If so, I direct you to: William H. Ingram, “The Ligatures of Early Printed Greek,” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 7:4 (Winter 1966): 371-396; William Wallace, “An Index of Greek Ligatures and Contractions,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 43 (1923): 183–93.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.2 (Winter, 2017).

David Weimer is the librarian for cartographic collections and learning at the Harvard Map Collection. His article on Harriet Beecher Stowe, political economy, and religion appeared in J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists and his exhibition, Where Disaster Strikes: Modern Space and the Visualization of Destruction, is on view at the Harvard Map Collection until April 2017 and at its Website. He received his PhD in English from Harvard University in 2016.